Het ontstaan van de Indo-Europese taalfamilie

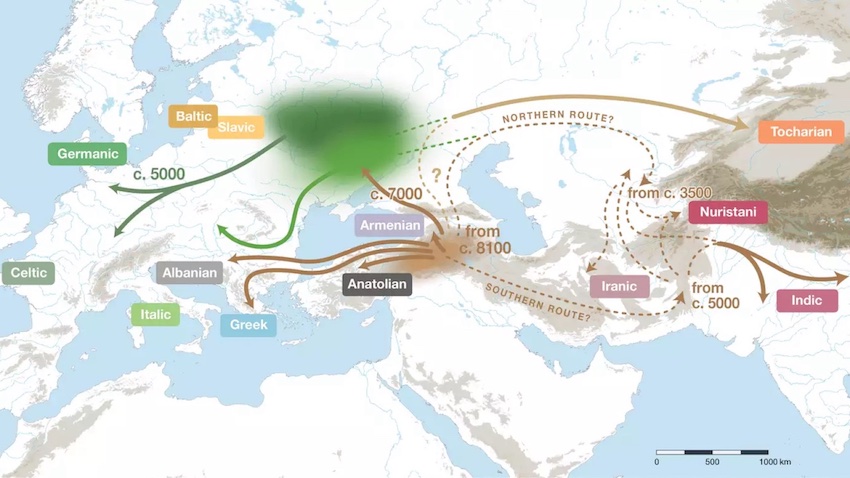

De Indo-Europese taalfamilie ontstond waarschijnlijk ten zuiden van de Kaukasus in een gebied, dat in de Oudheid het koninkrijk Armenië was.

Hoewel ruim drie miljard mensen een Indo-Europese taal spreken, weten onderzoekers niet zeker waar de taalfamilie vandaan komt.

Frank Jacobs, Science, 16-09-2023

Volgens nieuw onderzoek lag het thuisland van het Proto-Indo-Europees ten zuiden van de Kaukasus en begon de proto-taal zich ongeveer 8100 jaar geleden te verspreiden.

Bron: P. Heggarty et al., Science, 2023

Proto-Indo-Europees (PIE) is een taal die de oorsprong was van vele andere. Ongeveer 46% van de mensheid, ruim drie miljard mensen, zijn moedertaalsprekers van een Indo-Europese taal. Maar waar ontstond PIE voor het eerst en wie spraken het: veehouders uit de Pontische steppe die zich uitstrekt over Oost-Europa en West-Azië, of boeren uit Anatolië in Turkije? Op die vraag weten antropologen al eeuwen geen antwoord. En nu suggereren onderzoekers in het tijdschrift Science een derde plaats: de Kleine Kaukasus, die voornamelijk in Armenië, Azerbeidzjan en delen van Oost-Turkije en Zuid-Georgië ligt.

Grootste taalfamilie ter wereld

PIE is zowel de meest dode als meest levende taal. De laatste spreker stierf duizenden jaren geleden en als het ooit is opgeschreven, weten we er toch niets van. Het enige bewijs van het bestaan van PIE zijn de sporen die het heeft nagelaten in de talen die ervan afstammen.

Wij zeggen 'enige', maar dat omvat veel bewijs. Moderne afstammelingen van PIE zijn niet alleen Engels, Spaans en Russisch, maar ook Perzisch, Hindi, Bengaals en tientallen andere. Indo-Europees is veruit de grootste taalfamilie ter wereld. Het Chinees-Tibetaans, waartoe ook het Mandarijn-Chinees behoort, is op afstand tweede, met ongeveer 1,3 miljard moedertaalsprekers.

Een groot deel van een eeuw hebben taalkundigen gezocht naar aanwijzingen voor de oorsprong van het Indo-Europees vanuit de talen zelf. Met behulp van fylogenetische analyse - fylogenetica is de studie van 'evolutionaire relaties' in de loop van de tijd of het nu om organismen of talen gaat - hebben ze een vocabulaire voor PIE gereconstrueerd dat ons een idee geeft van de cultuur van de mensen die het spraken. We weten dat ze woorden hadden voor beer (bérōs) en gans (hénos), wilg (wélə) en honing (méli), en turf (pékus) en omheining (hórtos).

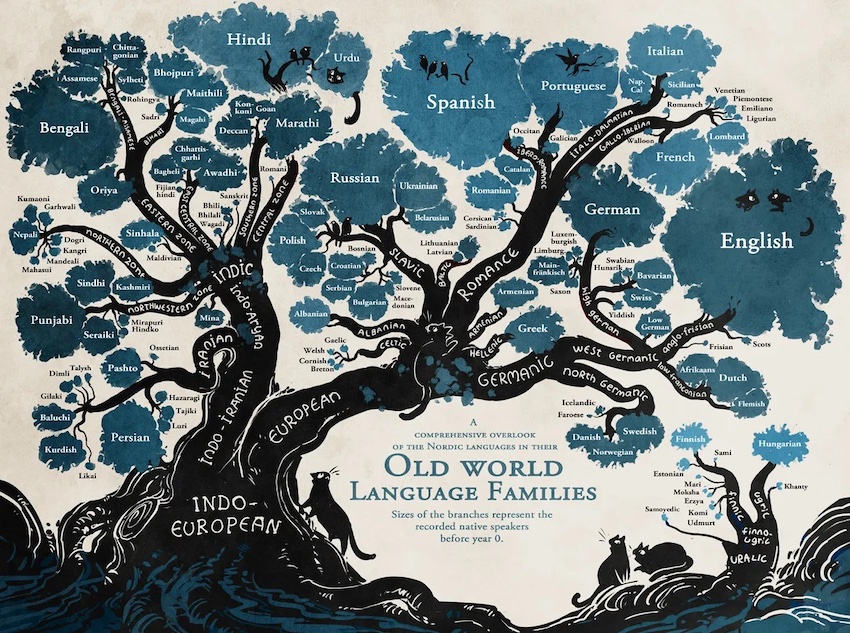

De taalfamilies stammen af van het Proto-Indo-Europees, mooi weergegeven als de takken van een boom, waarbij elk blad het relatieve aantal moedertaalsprekers van elke taal benadert.

Bron: Sta stil, blijf stil door Minna Sundberg

Oekraïne of Anatolië

Op basis van dergelijk bewijsmateriaal ontstonden er twee denkrichtingen. Eén ervan stelde dat PIE zo'n 6000 jaar geleden ontstond in de Pontisch-Kaspische steppe ten noorden van de Zwarte en Kaspische Zee, in de vlakten die zich uitstrekken van het noordoosten van Roemenië over het zuiden van Oekraïne en het zuidwesten van Rusland tot in het uiterste westen van Kazachstan. De nomadische herders die hier woonden, temden het paard, waardoor ze naar verre streken konden migreren. Dit wordt de steppe- of kurgan-hypothese genoemd, de laatste naar het lokale woord voor de prehistorische grafheuvels die in het hele gebied verspreid liggen.

Andere geleerden veronderstellen een ouder en zuidelijker begin voor PIE: ongeveer 9.000 jaar geleden in Anatolië. Dit schiereiland, ook bekend als Klein-Azië, begrensd door de Zwarte, Egeïsche en Middellandse Zee, is de meest westelijke uitbreiding van Azië. Tegenwoordig is het het Aziatische deel van Turkije. De theorie is dat de taal meeliftte op de verspreiding van de landbouw van hier naar grote delen van de Oude Wereld.

Waren de Yamnaya de oorspronkelijke Indo-Europeanen?

De kurgan-hypothese is de meest algemeen aanvaarde van de twee. Veel voorstanders denken dat PIE-sprekers, kurgan-bouwers en de oude Yamnaya-cultuur eigenlijk één en dezelfde zijn. Tegenstrijdig bewijs uit eerdere fylogenetische analyses heeft echter voorkomen dat de ene hypothese de andere volledig uitschakelt.

Daarom construeerde het Max Planck-team een nieuwe dataset van de kernvocabulaire uit 161 Indo-Europese talen, die uitgebreider en evenwichtiger was dan eerdere voorbeelden. Met behulp van recente ontwikkelingen in de fylogenetische analyse, schatten ze dat PIE ongeveer 8100 jaar oud was en dat vijf hoofdtakken zich ongeveer 7000 jaar geleden al hadden afgesplitst.

Armenië

De resultaten van het onderzoek passen slecht bij zowel de kurgan- als de Anatolische hypothese. Als oplossing stellen de onderzoekers een derde mogelijkheid voor: een vroeg thuisland voor PIE direct ten zuiden van de Kaukasus, waarbij één migratiestroom noordwaarts de steppe in gaat. Daar vestigden PIE-sprekers een 'secundair thuisland', van waaruit Indo-Europees 5000 jaar geleden de rest van Europa binnenkwam, met dank aan de Yamnaya en latere uitbreidingen.

Door een samenstelling aan te bieden van landbouw- en veehouderijtheorieën over de verspreiding van het Indo-Europees, suggereert de hypothese van het zuiden van de Kaukasus een oplossing voor een raadsel, dat de studie van Indo-Europees al zo'n 200 jaar achtervolgt. Wolfgang Haak, groepsleider bij de afdeling archeogenetica van het Max Planck Instituut voor Evolutionaire Antropologie, zei:

"Afgezien van een verfijnde tijdsschatting voor de totale taalboom, zijn de boomtopologie en de vertakkingsvolgorde het meest doorslaggevend voor de afstemming met belangrijke archeologische gebeurtenissen en veranderende voorouderspatronen, die te zien zijn in de oude menselijke genoomgegevens. Dit is een enorme stap voorwaarts ten opzichte van de elkaar uitsluitende eerdere mogelijkheden, naar een beter toepasbaar model, dat zowel archeologische, antropologische en genetische bevindingen integreert."

The Indo-European language family was born south of the Caucasus

Though over three billion people speak an Indo-European language, researchers are not sure where the language family originated.

Frank Jacobs, 16-09-2023

According to new research, the homeland of Proto-Indo-European was just south of the Caucasus, and the proto-language started to diverge about 8100 years ago. (Credit: P. Heggarty et al., Science, 2023)

Proto-Indo-European (PIE) is a language that gave rise to many others. About 46% of humans, well over three billion people, are native speakers of an Indo-European language. But where did PIE first arise, and who spoke it: pastoralists from the Pontic steppe straddling eastern Europe and west Asia or agrarians from Anatolia in Turkey? The answer to that question has been eluding anthropologists for ages. And now, researchers in the journal Science suggest a third place: the Lesser Caucasus, primarily found in Armenia, Azerbaijan, and parts of eastern Turkey and southern Georgia.

Largest language family in the world

PIE is both the deadest and most alive of languages. The last speaker died thousands of years ago, and if it was ever written down, we don't know about it. The only evidence of PIE's existence are the traces it left in the languages that descended from it.

We say 'only', but that is a lot of evidence. Modern descendants of PIE include not only English, Spanish, and Russian, but also Persian, Hindi, Bengali, and dozens more. Indo-European is by far the largest language family in the world. Sino-Tibetan, which includes Mandarin Chinese, is a distant second, with about 1.3 billion native speakers.

For the better part of a century, linguists have been looking for clues to the origin of Indo-European from within the languages themselves. Using phylogenetic analysis - phylogenetics is the study of evolutionary relationships over time, be they organisms or languages - they have reconstructed a vocabulary for PIE that gives us an idea of the culture of the people who spoke it. We know they had words for bear (bérōs) and goose (hénos), willow (wélə) and honey (méli), and peat (pékus) and enclosure (hórtos).

The language families descended from Proto-Indo-European beautifully rendered as the branches of a tree, with each leaf approximating the relative numbers of native speakers of each language. (Credit: Stand Still, Stay Silent by Minna Sundberg)

Based on such evidence, two schools of thought emerged. One proposed that PIE originated some 6,000 years ago in the Pontic-Caspian steppe located north of the Black and Caspian Seas, in the flatlands that stretch from northeast Romania via southern Ukraine and southwestern Russia into the furthest west of Kazakhstan. The nomadic pastoralists who lived here tamed the horse, allowing them to migrate far and wide. This is called the steppe or kurgan hypothesis, the latter after the local word for the prehistoric burial mounds that dot the area.

Other scholars posit an older and more southerly beginning for PIE: around 9,000 years ago in Anatolia. Also known as Asia Minor, this peninsula bordered by the Black, Aegean, and Mediterranean Seas is the westernmost extension of Asia. Today, it is the Asian part of Turkey. The theory is that the language piggybacked on the spread of agriculture from here to large parts of the Old World.

Were the Yamnaya the original Indo-Europeans?

The kurgan hypothesis is the more widely accepted of the two. Many of its proponents think that PIE speakers, kurgan builders, and the ancient Yamnaya culture are actually one and the same. However, conflicting evidence from previous phylogenetic analyses has prevented either hypothesis from completely knocking out the other.

So, the Max Planck team constructed a new dataset of core vocabulary from 161 Indo-European languages that was more comprehensive and balanced than previous samples. Using recent advances in phylogenetic analysis, they were able to estimate that PIE was approximately 8100 years old, and that five main branches had already split off around 7000 years ago.

The study's results fit poorly with both the kurgan and Anatolian hypotheses. As a solution, the researchers propose a third possibility: an early homeland for PIE immediately south of the Caucasus, with one migration veering off north into the steppe. There, PIE speakers established a "secondary homeland," from where Indo-European entered the rest of Europe beginning 5000 years ago, courtesy of the Yamnaya and later expansions.

By offering a hybrid of the farming and pastoralist theories about the spread of Indo-European, the south-of-Caucasus hypothesis suggests a solution for an enigma that has dogged the study of Indo-European for about 200 years. Wolfgang Haak, group leader at the department of archaeogenetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said:

"Aside from a refined time estimate for the overall language tree, the tree topology and branching order are most critical for the alignment with key archaeological events and shifting ancestry patterns seen in the ancient human genome data. This is a huge step forward from the mutually exclusive, previous scenarios, towards a more plausible model that integrates archaeological, anthropological, and genetic findings."

terug naar het overzicht

terug naar de Kelten en Armenië

terug naar het weblog

^